March - April 2020

In the span of a few short days in March, life as we know was irrevocably altered, and the long, meandering weeks that followed tested our collective patience and swelled our most pressing anxieties. Movement halted, activity grinded to a halt, and businesses that brought our community closer were shuttered until further notice.

Fountainhead’s plans were thwarted too. Our Open House - a beloved event that invites the public to interact with our resident artists, and get a firsthand look at the work they made during their residency - was canceled. Our March Artists-in-residence - Amani Lewis, Qinza Najm, and Norberto Rodriguez - found themselves deciding whether to rush home to their families, as Amani did, or shelter in place in Miami, as Qinza and Bert ultimately decided to do through April.

We are presented, then, with a radical experiment unlike any we have experienced in our history. Our resident artists are generally met with endless opportunities for connection and dialogue, conducting countless studio visits, meeting new supporters and patrons, and visiting the vast majority of Miami’s cultural institutions and businesses. Instead, Qinza and Bert found themselves confined to their shared home, with most in-person activities strictly prohibited, their daily interactions limited to virtual hangouts, and, those with each other.

Fortuitously, two artists whose practices couldn’t be more different found themselves leaning into their creative differences as COVID-19 left them no choice. Here, we have Bert, an artist whose practice is quiet and meditative, and centers on digital oversharing and living his daily life online; sharing space with Qinza, an artist who emphasizes the role of the viewer in her work, gathering participants within her installations to talk through their experience with a particular topic.

In this setting, both are learning to meet somewhere in the middle, with Qinza leaning into Zoom as a tool for this continued connection. “It’s so interesting to be renegotiating how we interact with people in our studios, it’s a moment of transformation and we’re thinking about finding new solutions and new ways of being,” she says. Bert is reconsidering physicality as an aspect of his practice. “I once married a total stranger off the street, and this somehow feels like an opportunity to delve back into that type of project,” he says.

Despite their altered conditions, the artists maintain that the residency has been an utterly nurturing environment - perhaps now more than ever. “It is genuinely one of the most unique and transformative residencies I’ve ever done,” says Qinza. “It’s everything an artist can ask for, Dan and Kathryn are so cool and supportive and they’re really amazing people. It’s pushing our boundaries to rethink things and recreate solutions to issues.

Through portraiture, Amani Lewis attempts to rewrite the black experience. With a practice grounded in observation, Lewis draws from real world subjects that form part of the urban fabric of their immediate environment. They depict these figures in saturated mixed media works incorporating textiles, glitter, collage and screenprint. Their paintings elevate their subjects into a heroic context.

As an artist who moved frequently with their mother - living most of their adolescent years abroad in Colombia - Lewis didn’t fully step into their own black identity until they moved to Baltimore to attend art school at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Being surrounded by a predominantly black community made them realize their perspective needed to shift to consider the systemic inequalities that affect African Americans.

One that caught their attention was the notion that black Americans simply weren’t used to seeing images of themselves in art history. “I had a show in Pittsburgh before and these little kids started seeing the sculptures and paintings, and said, ‘This is why I don’t go to museums because I only see white people’ - and really when you’re in an exhibition of Expressionism or Impressionism, black people are not the main subject,” they said. “So I started thinking about painting as a way for people to see themselves represented.”

They began to observe the people and places they came across in Baltimore, a city where the signs of racial inequity are left bare for all to see. Neighbors, squeegee boys, and passerby are quickly sketched into a one-line drawing, a method that Lewis equates to tracing their lineage as an African American. “I’m tracing their characteristics and feeling closer to that person because of it,” they say. Those one-line drawings are then infused with color blocking, textile, and screenprint to create a vibrant collage that mirrors the complexity of the figure’s history and inner life. Often, these subjects are depicted within nature, like in Lewis’ prominent series “Negroes in the Trees.”

Lewis’ time at Fountainhead was unfortunately cut short, as the pandemic and a simultaneous personal issue called them back to Baltimore. “I do plan on coming back to Miami, because I met so many people there that I would like to collaborate with and get to know better,” they said.

Qinza’s introspective practice builds on decades of experience as a practicing psychologist, and a childhood and adolescence governed by a restrictive society. Growing up in Pakistan, Qinza’s upbringing reflected the country’s oppressive attitudes toward women, with her perspective on gender roles and relationships substantially influenced by these societal tendencies. Thrust into an arranged marriage, Qinza moved to New York, where she studied under Larry Poons at the Art Students League and applied an innate understanding of the human psyche to her work.

“I’m interested in personal transformation, empathy, and healing, both seeing it in other people and in the idea of awareness and how it informs our daily existence and relationships,” she says. “As an artist, I am interested in making a difference; I want to create a bigger dialogue on a global scale, and have conversations about difficult topics.”

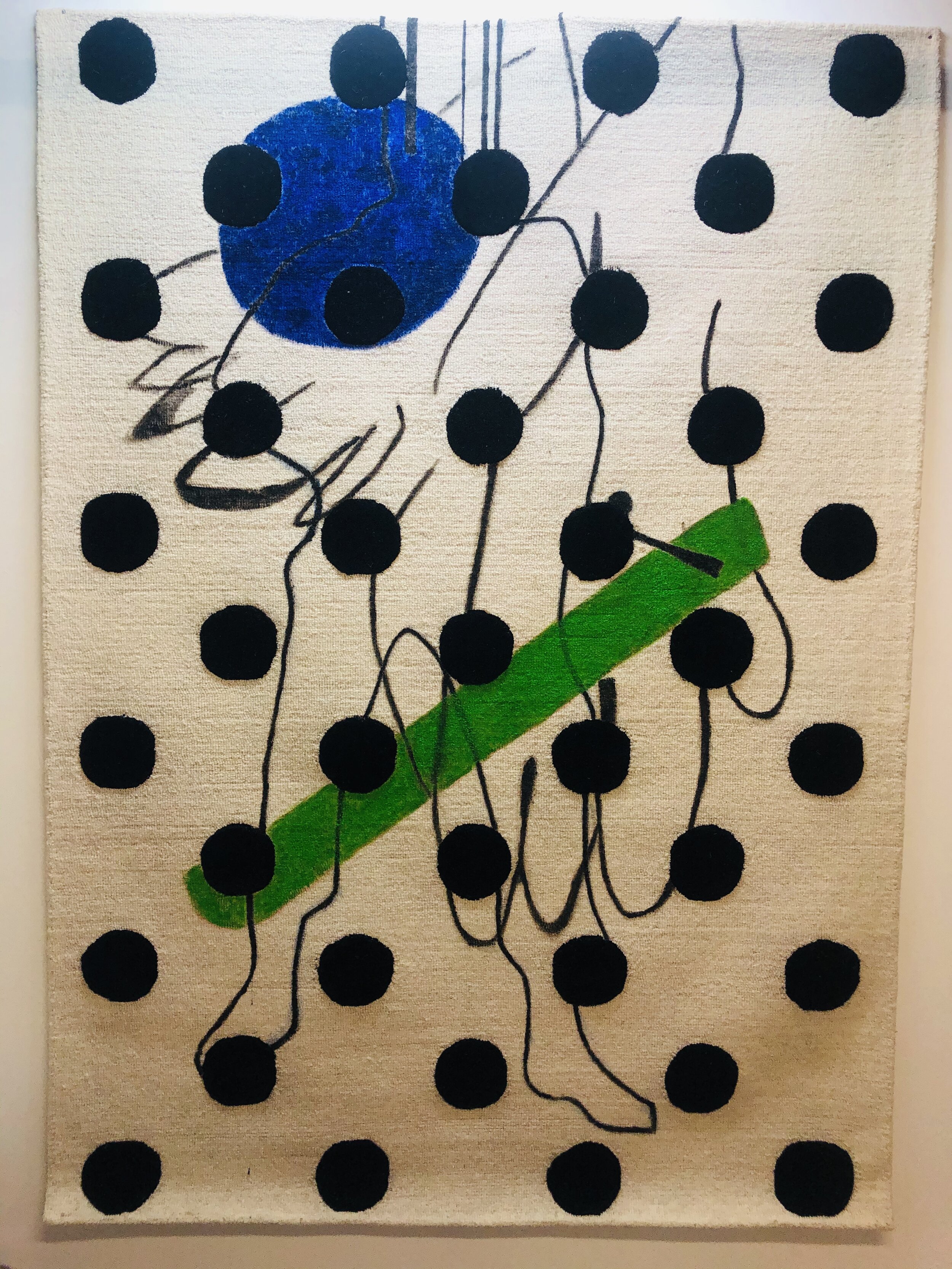

Subverting any one medium in favor of experimentation with many, Qinza’s works have touched on a broad range of topics, from sexual battery to gun violence, border abuse and misogyny. Generally, her work seeks to address the fragility of mental health when faced with these pressing issues, and incorporates multiple layers of art practice in order to drive her message forward. In one work, she covers herself in a veil of roughly 1100 bullets - one for both every woman murdered in an honor killing in Pakistan that year, and every child murdered in an American school in 2016 - and sits on a woven red carpet, sourced from textile makers in her native land, ensuring that each nation’s complicity in widespread violence isn’t merely swept under the rug. In another, she uses a traditional woven carpet (a frequent material throughout her practice) in a collage of a squatting female form, leaving to interpretation whether her posture is lewd or generative, while reclaiming the form by using an act of objectification to address women’s financial, reproductive, legal and social rights. In more recent work, Qinza focuses on her own vulnerabilities, creating installations that invite participants to reflect on the evolution of romantic relationships in the digital age.

At Fountainhead, Qinza is returning to painting, allowing her gestures to be guided by raw emotion and expression. “It’s almost childlike, because I feel like that’s what we need to get through this particular moment and get back to basic existence” she says. A new series, Forbidden/Healing Touch, incorporates our present anxieties about illness transmission with figurative shapes alluding to the absence of physical touch. “As an artist, I am becoming more radically vulnerable in my art practice and opening up a lot more about my personal experiences,” she says, “and this has been an opportunity for me to dive deeper into that.

Norberto Rodriguez’s multifarious practice builds on a long and frequently overlooked art historical tradition of commodifying the artist over the artwork. Artists like Andy Warhol - who essentially pioneered reality television by making films chronicling the mundanity of the everyday - inspire Bert to turn the lens onto himself, and makes performative, time-based artworks that spotlight an important component of the human condition.

He married - and stayed married to - a total stranger off the street for a year. He’s given free 10-minute foot rubs to anyone that walks through the door. He’s hired a private eye to spy on his entire family, and convinced a friend to secretly hire a private eye to spy on him. Lately, he’s taken to broadcasting himself on a webcam within his room, producing a Truman Show effect that questions the divide between public and private life. Through these works, Bert is less interested in highlighting society’s voyeuristic nature, than he is bringing to light the inner workings of the mind of the artist. The artwork isn’t the product here - it’s the artist and their innate sensitivity to the world around them.

“I look at my work as though I’m manipulating reality like a painter manipulates paint,” he says. “Part of it is switching the focus from artwork to artist, because the way we define art is we define it by the product. Because I started out performing and doing things in physical reality, it’s lead me to this place where I treat every aspect of my life as if I'm making art. I believe the artist is the true asset.”

At Fountainhead in a moment where everyone is tuning in online, this is certainly Bert’s moment. It’s possible that this global pandemic will ultimately usher in a new era for artists, one where Instagram transitions from platform to medium, and Bert is exploring that as a new approach for reaching and communicating with his audience.

“This is what I have been planning for the last 10 years, for everyone to live on the internet,” he says. “To know what that’s like. To transition and understand that an evolution is happening and we are transitioning to the matrix. This is planting the seeds that our quality of life can be very different.”