December 2020

Images Courtesy of Alex Nuñez

Words by Yadira Capaz

When entering the home of The Fountainhead Residency, one enters a living way of relating to art. Here, art is co-creation in community. The works breathe in the space between the rich lived experience of the artists and the abundance of conversations with curious guests that fuel the momentum of their material creations. Their host, Kathryn Mikesell, notes that this December “may stand out as the month with the most one-on-one conversations yet” in over 12 years of the residency. This special quality is a direct result of our adaptations to the pandemic calling for more intimate connection, and Miami Art Week going underground after public cancellation.

The artists in residence for December 2020 bring vivid dialogues about embodiment, color, and architecture to the Miami arts ecosystem. Hailing from Pennsylvania, Shikeith is inspired by his experiences as a queer Black man in America to create photography, film, and installation art that explore liberatory embodied expressions as they manifest in individuals often denied the depth of their interiority. Malaika Temba remixes the evocative colors of her native Tanzania in textiles that juxtapose the complexity of her emotions with nuanced colonial histories. Experiences in confined spaces and the military in Israel influence Zac Hacmon to play with sculpture to open inquiries about the social politics embedded in architecture.

Shikeith noted that “all three of us often make large-scale, institutional art, which is not the typical fit for the commercial gallery system.” Yet their time at the residency began with a marathon of conversations with gallerists still visiting for an informal Miami Art Week. These artists welcomed the challenge to refine how they talk about their work, and think about how they relate to the business of being an artist. “Here in Miami we had long conversations on the fundamentals of art making,” comments Zac. The Fountainhead Residency not only offers artists space and time to create their work, but also a fertile social world to develop their ideas and make connections as they visit cultural sites across Miami. Zac found particular reassurance in visiting The Margulies Collection, for example, because he was able to encounter collectors who value large-scale installations like the ones he makes. Malaika expressed her gratitude in clear terms, “Kathryn is a very big connector,” before rushing off to a meeting with a gallerist.

It’s the ample time for conversation that struck these artists the most, and perhaps a secret ingredient in the accelerated growth the residency provides to artists in the early stages of their career. “I learned a lot by hearing Shikeith and Malaika talk about their work, and I’m fascinated by their approach,” Zac shares. For Malaika, it was the post studio visit wind-downs that opened the connection among the three. She says, “We are comfortable with each other. The passion and depth is there, there doesn’t need to be a front. There is no competition, no one is too hype, and our personalities are equally chill.” The transmissions also happen organically from co-working together, sharing dinners with the Mikesells like a family, and learning from observation, or as Shikeith puts it, “listening for the objects.”

Shikeith is awe-inspiringly passionate about the mission of his art practice: “There is a sense of self within us that has been robbed of expression from many generations of Black queer men, and my work is about loosening up the grip of those histories whether we have to sweat it out or dance it out. It’s about going through that to get to a future utopia where we can just be.” He returns to Miami after spending time at Locust Projects last year creating uncanny portraits of Black men full of vulnerability and emotion. At the Fountainhead, he continues with the portrait series in a photo studio off-site, and is taking advantage of his proximity to water to create dance films with models he recruits from his Instagram open calls. On the wall of his research room in the Fountainhead home he has a collage of movements that inspire the choreographies he is seeking to capture with gestures that point toward jazz improvisation and Alvin Ailey’s performances.

“I am working on building a visual code and developing a language for my practice,” Shikeith explains. Water is one of the recurring symbols in his work, as is the color blue, and both resonate deeply with his own ancestral history. Water to him represents “channels of turbulence and refuge” that echo deeply with the history of the Atlantic slave trade and the Underground Railroad. Blue spaces emerge from a research obsession with the practice of painting thresholds with haint blue which he explains as a “ghost-tricking phenomenon that would prevent evil energies from entering into interior spaces,” and is a nod to “the ephemeral presences that continue to haunt Black queer men.” It was eerie to hear he eventually found out that his ancestors had worked in South Carolina where the indigo for haint blue was grown. He merges this personal history with his research to guide the direction of his work. “We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity” by bell hooks rests on his desk, and he cites an artistic lineage of Black gay men including Isaac Julien and Marlon Riggs as inspiration.

Shikeith has a background in fashion photography, and points to the Black Lives Matter movement and encountering the work of Renee Cox as the moments that “shifted [his] imagination of what a photo can achieve.” Because his work is so connected to his identity, early on he considered the question of whether to work with self-portraits or surrogates, but he found himself focusing more on portraits of individuals for their unique expression. After an MFA from Yale in 2018, he is now reimagining portraiture through large-scale installation art as a way to queer forms of viewing. For example, for an upcoming commission from MOCA Cleveland, Shikeith is using his time at the Fountainhead to design a film split among various screens that look like the sails of a sinking ship. The film features a fierce 8-year-old boy dancing majorette which is historically a woman’s dance popular on HBCU campuses. Shikeith explains that “the idea began with me filming this young boy sinking this ship, sinking and destroying a system that tells him he can’t dance like this, he can’t move through the world like this.” He admits he saw himself in the young boy. Shikeith was once a shy child, but he says his mother would push him into many dance competitions, and he would win.

Shikeith continues to pursue this love of movement through his collaborations with models turned dancers. He mentions that there is a “special quality of Black men from the South in how they dress and embody femininity,” and appreciates the culturally diverse diaspora Miami holds. The Black spiritualities that thrive here emerge in the dance films he is shooting by the water in Morningside Park and the Deering Estate. He waxes poetic about “loosening up the rigidness of masculinity” in the presence of water, how “Black people are parables of the sea,” and relishes in “being mutable but sustaining and flourishing beings despite how much of us is tried to be policed or contained.”

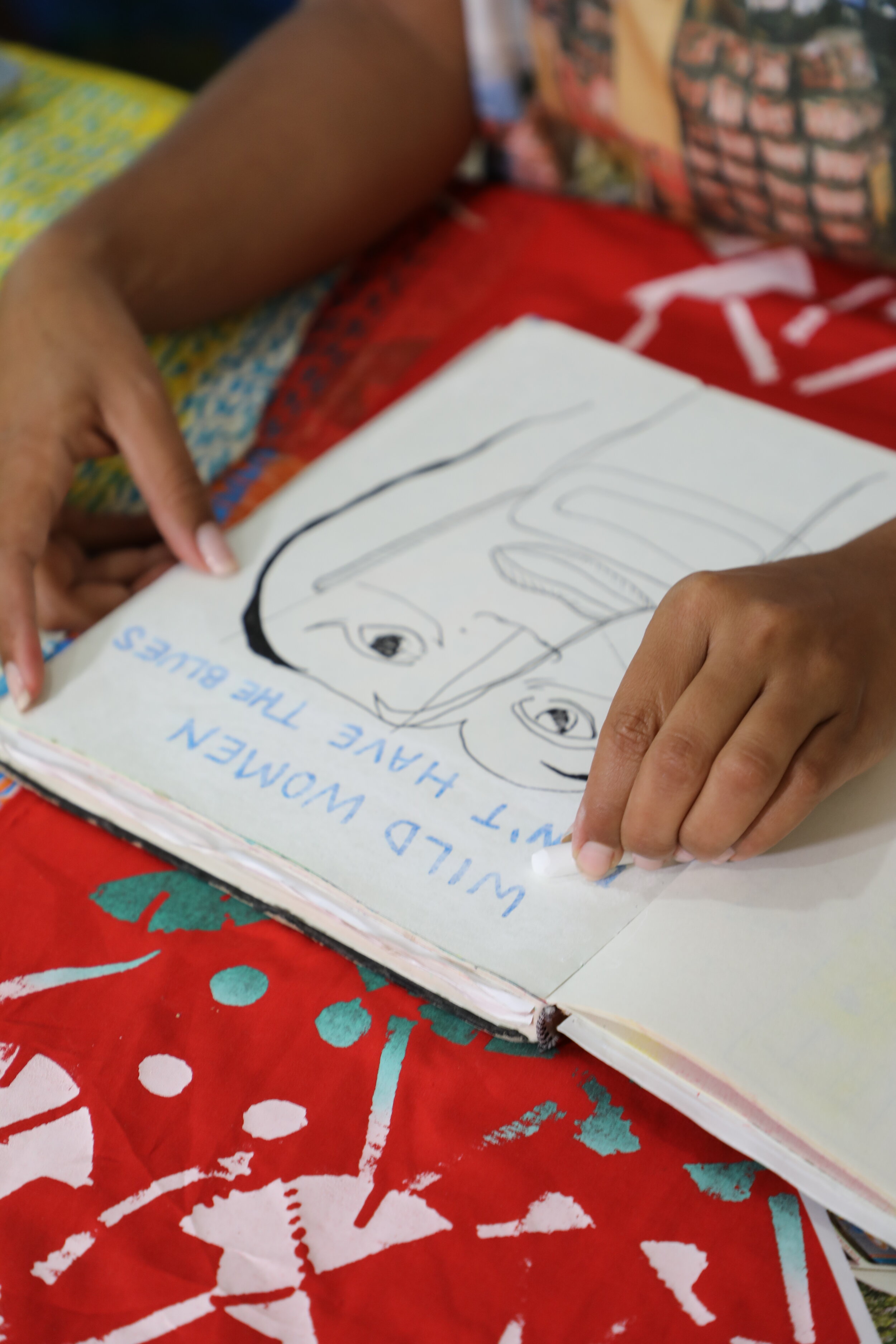

Walking into Malaika Temba’s studio is an immediate visceral immersion into a colorful world of rare shades and stimulating contrasts. She has covered every wall and desk in her studio with her vibrant textiles. “I like to use color that confuses people’s brains,” she says with glee. A closer look reveals that she has carried a large chunk of her body of work with her to Miami, and is actively creating new pieces on site from screen-printed fabric. Hazy curtains of bloody reds, dark greens, mustard yellow and rusty brown on one wall eventually reveal a Tanzanian creation story she is collaging into a piece on the adjacent wall full of shades of blue and burnt orange inspired by a photograph of a bus she saw on a recent visual research trip to her homeland. Text is alternately blended into hiding or loudly centered in heavily textured jacquard loom pieces on the remaining walls. She programmed these designs on a computer to weave new colors by combining threads. The overall effect of being in her studio is mesmerizing.

Only two years have passed since Malaika received her BFA from RISD in 2018. She spent that formative time working for fashion label Pyer Moss in NYC doing surface design development and leading visual storytelling in creative direction. She left her role there right before coming to the Fountainhead Residency, now fully focusing on developing her portfolio to pursue an MFA. Malaika returns to Miami as a YoungArts alum with the support of the organization.

She is fascinated by advertising and graphic design outside of America in general, but especially in Tanzania. “I am interested in exploring traditionally handmade craft with digital aesthetics,” she explains.

Without a doubt, Malaika identifies as a “maximalist” in a world full of standardized minimalism, and the more she opens up to talk about her work, the more a political resistance emerges as a foundation. In relation to Tanzanian visual culture, for example, she criticizes how “The influence of tourism acts as a form of colonialism. The locals welcome it to stimulate the economy, not for erasing their identity.” In this light, her recent series takes a stance in preserving the country’s aesthetics. There is nuance in her inquiry: “African girl speaks in English accent” is written in the center of a work in progress. These haunting textual fragments feature prominently in her work, often inspired by the work of Ntozake Shange whose writing expresses so much complexity about what it means to be a Black woman and the emotional labor it entails. One of Malaika’s pieces is humorously titled “For East African Girls who have considered self-worth when Drake is not enuf” as an allusion to Shange’s famous choreopoem. For Malaika, “color is a vehicle for emotion.” The combination of subtle text and rarely seen shades of color reflect a complex emotional landscape. “Emotion is not weakness. It’s the reason I am inspired and relate to people,” she asserts.

During her residency Malaika has been digesting the Art Deco pastel color palette and the vibrant Caribbean influence of Miami’s “color lifestyle,” as she calls it. She has also been reflecting more on the business side of an art career after so many conversations with gallerists, and feeling clear in her commitment to being an artist full time by pursuing an MFA. She hopes it will help her build more of the academic language she uses to talk about her work, which she had a chance to practice a lot while being here. After Miami, she’s headed back to New York City, and perhaps to another trip to Tanzania with her dad when the pandemic passes. Reflecting on where she is in her artistic process, Malaika says “I need to be less picky, and I need to get more of my ideas out so I can develop them visually. I spend a really long time writing notes and doing research and distilling a thousand ideas into a few ideas for a piece. I think I just need to make a thousand pieces instead.”

Zac Hacmon

“To play is a political act,” says Zac Hacmon, inspired by Italian theorist Giorgio Agamben’s idea of irreverent “profanations” in the book “What is an Apparatus?” There is a fun element of surreal play in Zac’s work that is hard to notice at first because the pieces address political histories with the austere visual language of institutional architecture. When trying to briefly summarize his practice, he explains “I am interested in developing a language of formal and architectural structures in order to confront sociopolitical issues.” He is from Israel, born to a family of Libyan-Jewish refugees, and identifies a lot with the influence of growing up under the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “Displacement, territory, and the meaning of home are themes I work with and challenge,” he says. Zac spent 3 years in the military and 2 years as a security guard before redefining himself as a sculptor and installation artist with an MFA from Hunter College in 2018. Now based in NYC, he welcomed a residency in Miami during wintertime amid the pandemic with a big sigh of relief.

Zac slowly but surely transformed the garage studio at the Fountainhead home over the course of his residency. He arrived expecting to work on 2D sketches for future pieces, but he quickly realized he needed to work hands-on with 3D sculpture to feel fulfilled. Thankfully Kathryn took him on a shopping trip to the hardware store to get the ceramic tiles and metal railings that compose the sculpture at the center of his studio now. He needed to paint the floor white to create a more sterile environment before he could start creating. Around the room are paper capsules, cardboard prototypes, and digital drawings of people laying inside his sculptures - some are even reimagined in red to resemble Tetris blocks! In a moment of vulnerability, Zac shared his personal connection to the materials: “The ceramic Subway tiles comforted me in a time of distress. It was during my second year in New York as an immigrant. I had a breakdown in the subway and the closest thing surrounding me were the 4x4 inch white tiles.” According to him, these same institutional tiles are also used in schools, detention centers, and jails.

Zac prepared a digital slideshow of his portfolio to present to his guests in order to provide a fuller perspective of how his practice has evolved. The first piece he shares is “Take Me Back,” which is a collection of 39 mattresses gathered from the streets of Tel Aviv with a tunnel carved through them by taking out their core. He wanted to invite reflections on discomfort, how objects can become useless, and the preciousness we feel toward certain objects that soon become disposable when they are replaced. He also shares a series of surreal “Capsule” pieces that warp space according to his body measurements. These were inspired by the double-sided mirrors in the architectures of surveillance he encountered at Hunter College. They provoke a longing to feel what it would be like to be inside them, and Zac explains that “Inaccessible does not mean it’s not interactive. The temptation is unfulfilled and that is the interaction.” In “Study of a Gateway,” Zac recreates narrow black metal barricades similar to the border checkpoints between Palestine and Israel to draw attention to how, in his own words, “the architecture takes away identity and turns people into animals.”

Zac’s body of work reflects a growing social conscience and a desire to use his inquiry of architectural spaces to shine a light on important issues. Most recently he has begun to add a participatory community-building element to his practice. In the past year he finished a piece that involved research and volunteer work at the US-Mexico border interviewing indigenous migrants from Casa Alitas and Humane Borders volunteers. While at the Fountainhead, Zac is preparing a proposal to collaborate with refugees from a center in Harlem in order to create a sound installation together that shares their stories through the air vents of his sculptures. He wants to secure grant funding to pay participants for their time. Balancing a social practice with artistic output while navigating the financial landscape of being an emerging artist is a lot. Zac tries to stay grounded in how refreshed he feels in creative moments. “I’ve been enjoying opening up the garage doors during the day, and letting nature in as I work,” he says.