August 2020

Images Courtesy of Alex Nuñez

Words by Nicole Martinez

August’s resident artists found themselves in a happy coincidence when one of Fountainhead’s curatorial board members approached Danielle de Jesus with an unconventional proposal: Would she like to spend a month in residence at Fountainhead in Miami, and might she recommend two other artists to come along for the ride? She called upon her friends and fellow Yale MFA students Chiffon Thomas and Bhasha Chakrabarti to make the 20 or so-hour journey and spend the final dregs of summer sharing a home and studio. While Danielle and Bhasha had shared a studio space before, living together would be a new experience - and the usually reserved Chiffon would be stretching themselves in new ways. That would prove to lend proof to what we’re quickly learning at Fountainhead - that bringing three friends into a common space sets the experience on a creative and emotionally enriching path.

“I typically don’t like being thrown into situations with new people,” Chiffon says. “I probably would have been a lot more distant or closed off or hard to get to know, and less open to even sharing ideas in a studio or getting feedback in a way that I felt comfortable doing with Bhasha and Danielle.”

Freedom of expression reigned as the artists found themselves unbounded in both the studio and online, sharing their experiences on Instagram as they immersed themselves in the cultural experiences Miami had to offer while the city’s institutions started to reopen. “The outings for me were an opportunity to bond with the city’s makers and it was incredible to see art in person after such awful times,” says Danielle.

Chiffon and Bhasha, in turn, were particularly inspired by the feedback they received from both curators and artists in our community.

“Being here and seeing what curators are interested in and drawn to or chose to elaborate further on was pretty enlightening,” Chiffon says. “It’s nice to catch a glimpse of their mind and have their attention in such a small group.”

“I think that a lot came out of conversations we were having, both in terms of technique and also conceptually,” says Bhasha. The pacing of having others around was really different and changed what I could accomplish, and all of the feedback and input I was getting has really shown through in my work.”

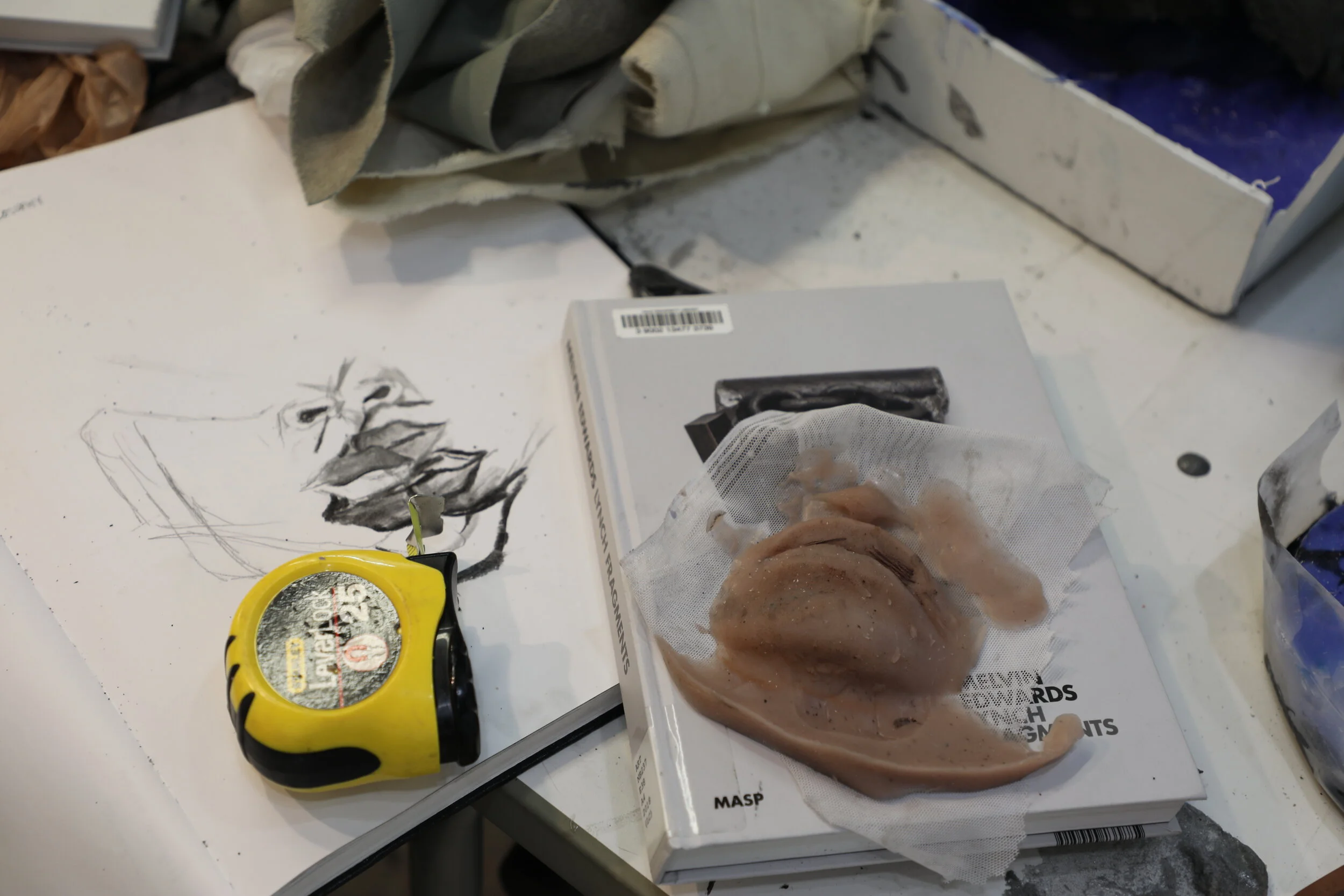

Bhasha’s artistic practice is a metaphor for her need to mend what’s broken. Working primarily with textile and traditional craft processes like quilting, Bhasha transforms these oft-overlooked artistic traditions into a contemporary exercise of repair. Often rendered in the tradition of Gee's Bend quilts, with abstract shapes creating a puzzle of color and texture, Bhasha often intervenes reclining female figures into the work, as a means of questioning conventional portrayals of women in art history.

As an Indian immigrant living in Hawaii - a state where indigenous cultures and histories are disenfranchised to create an exoticized notion of the island - Bhasha has always been interested in mending these ideological rifts. Studying political science and economics in college, her career began in philanthropy before a brief stint in advertising exposed her to the world of contemporary art. Examining art historical traditions and feeling an urgent need to connect to her own Indian heritage, Bhasha decided to quell her thirst for the two, moving to India to attend art school. There, her interest in exploring the colonialist dynamics that continue to intersect in our globalized world were brought to the fore, as she took to examining how the textiles and used clothing industries infiltrate that system to perpetuate the exclusion of women.

“In India, I was fascinated by the used clothing industry, particularly because Indian women are usually the ones making or mending clothing, but because used clothing was considered ‘commercial’ since it is resold for profit, it was something that only men were allowed to work with,” she says. “At the same time, in Western traditions mending used clothing is often considered ‘women’s work,’ and it’s not ever considered artistic or creative. I just became interested in why something I saw as radical change - you are fixing something because you hope you can fix it - isn’t considered creative.”

With the bulk of her practice today centered around repairing or refashioning textiles, Bhasha reclaims the female gaze and elevates craft to a contemporary art form. At Fountainhead, she continued developing the integration of female figures on her quilts - a relatively new direction in her work - with input from her fellow residents. “The energy and feedback from the other artists in the space was pivotal for me in coming to terms with what I want,” she says. “Watching them work and collaborating with Chiffon also reminded me of what I can take from that process and put back into my own work.”

Danielle de Jesus looks to the past not with nostalgia, but with care. Growing up in the predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood of Bushwick as gentrification was quickly gaining speed, Danielle resurfaces old photographs to rewrite a story about displacement into one about resilience. Turning these photographs into warm, hyper-realist figurative paintings - rendered on materials like linen, fabric, and currency - Danielle’s work transcends the physical borders separating the island from the diaspora, focusing instead on honoring a people whose spirit cannot be squashed.

“When I make these pieces it’s more of an archive of what I remember pre-gentrification. I don’t want to focus on the effects of what happens to these people because I think their stories are much more interesting than their displacement,” says Danielle.

Danielle, who started out as a photographer, has been documenting her surroundings from a young age, and much of those photos today are the jumping-off point for her large-scale paintings and mixed media works. While she studied photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology, she is an entirely self-taught painter, and uses much of what she learned about manipulating light and warmth through a lens to create her paintings. She looks at her photographs as ‘sketches’ of the painting she will ultimately create.

“When I go through the archive I think about what this picture means to me, what I remember, who was this person and what do they represent?” she says.

Danielle often incorporates unconventional materials like currency, curtains, or police tape into her paintings as a means of exploring the inequities that often lie beneath the surface of persistent issues facing marginalized communities. Her viral cash paintings, often painted on a $1, $5, or $10 bill, draw attention to the fiscal policies that govern Puerto Rico’s position as a territory of the United States. Adding media like police tape to finished paintings highlights segregation faced by black communities.

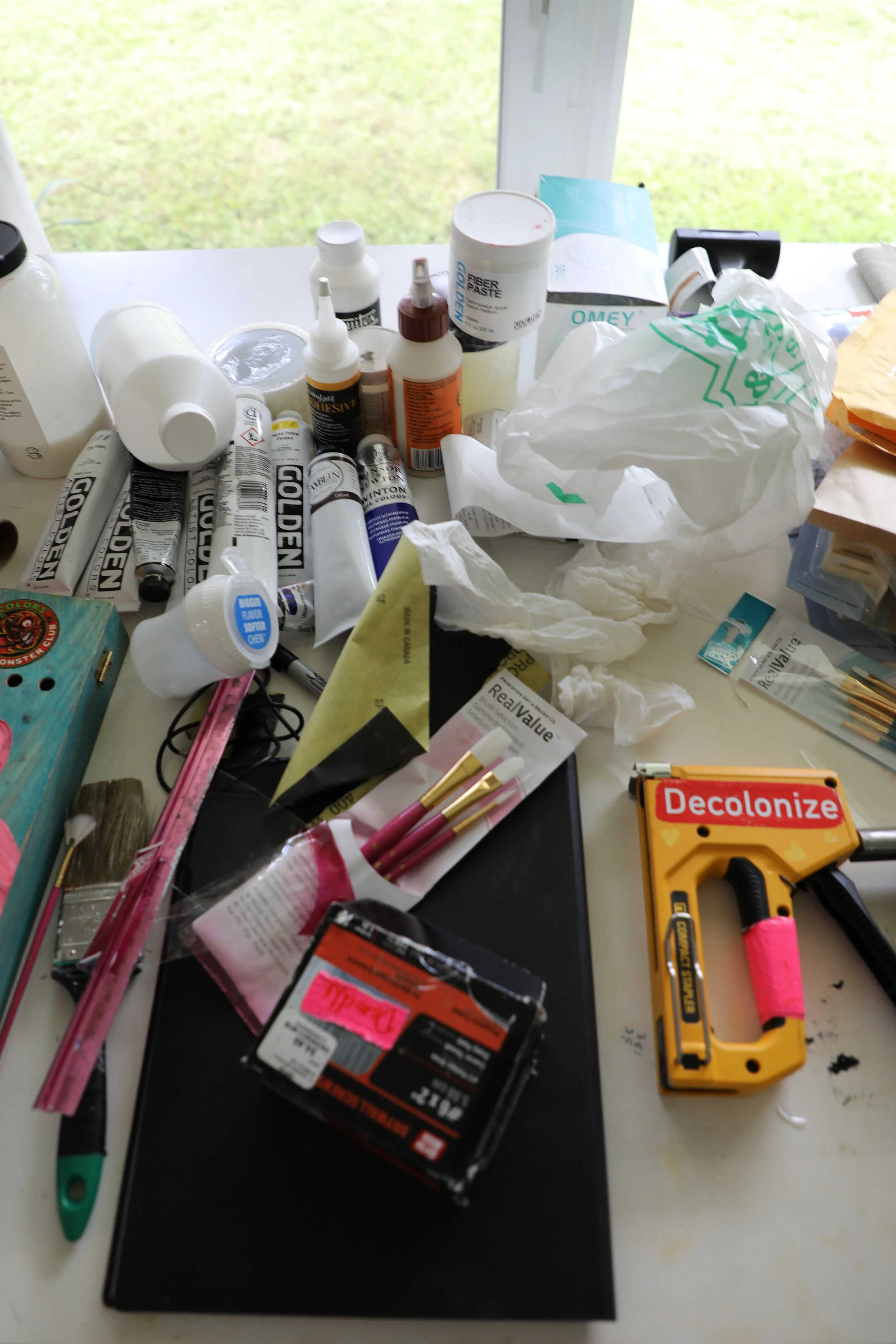

At Fountainhead, Danielle continued to focus on this aspect of her work, noting that she is interested in following a similar process with all of the communities that have a place in her heart. From documenting Black Lives Matter protests in New Haven, where she currently resides, to witnessing the fish kill event here in Miami - sparking a gaze toward human environmental destruction, Danielle considered how new techniques might be applied to discuss these issues carefully and sensitively. “Seeing the human effect we have on the earth...was a huge learning. Now, whenever I throw something away in the trash I think about where it's going to end up,” she says.

In creating works that distort materials, histories, and images, Chiffon Thomas illuminates the interiority of an individual, questioning the need to obscure identity in favor of societal conformity. Deeply personal in nature and often springing from their lived experiences and family dynamics, the specificity of Chiffon’s work takes on a universal approach as they expose these psychological mechanisms as tools of oppression. Approaching their work from that context, Chiffon creates mixed media sculpture and embroidered textile works that meditate on relational turmoils that are unwittingly destroying our sense of self.

“I’m interested in human behavior and understanding addictions and attachment theories and how people develop into the person they are,” says Chiffon. “How do you find a sense of acceptance? How do you work through these characteristics that aren't always accepted?”

By focusing primarily on the body and grounding the subject matter of their work in research and family memorabilia, Chiffon’s practice appears like painstaking emotional labor that the artist takes on with tremendous sensitivity and a self-proclaimed ‘hyperawareness.’ They often revisit old family albums, finding particular looks or gestures that reveal a hidden memory or internal turmoil. In recreating those moments through a time-consuming practice like embroidery, Chiffon can spend time contemplating how it can be altered to reflect the inner truth locked within.

The same is true for the bibles Chiffon manipulates to resemble faces or body parts trapped in cages, tearing apart leather, paper, and thread and incorporating plaster to mold these sculptural works into semi-figurative creations. While they may appear to be a representation of the artist, they in fact hope that viewers will project themselves into the work to free themselves from repression, or the feeling that they couldn’t be who they wanted to be due to the material contained within the work’s original form.

At Fountainhead, Chiffon built upon on existing works by experimenting with new materials and processes, and spent time revisiting old family albums and conducting research in an effort to put forward new ideas for work. Noting that the time they spent speaking with curators was invaluable, Chiffon says they’re coming away from their time in residence with a new approach to making work.

“I ask myself all the time, is the art doing enough? Does it compensate for any circumstance? When it stays with people in their psyche where they feel drawn or compelled to speak about the work, it’s a reminder that it did something for someone in particular.”