October 2020

In studio images courtesy of Alex Nuñez, Open Studios via World Red Eye

Words by Nicole Martinez

At the core of Fountainhead’s mission is the belief that artists and their work can shift hearts and minds toward a more hopeful and equitable future. With that in mind, we initiated our first thematic residency around the topic of immigration, generously sponsored by the Shepard Broad Foundation. October’s resident artists were selected by a jury of Fountainhead alumni and local curators who are immigrants themselves. Their truly outstanding selection of artists - Arleene Correa Valencia, Victoria Idongesit-Udondian, Marton Robinson and Daniel Shieh - were welcomed to Fountainhead this month.

With each artist representing a diversity in practice and perspective - some, like Arleene and Victoria (who participated virtually), take more obvious stances on ideas around immigration in their work; while Daniel and Marton reflect more subtly on their experiences as people of color - their time was marked by an active schedule of discussions designed to introduce our community to their own. Miami is certainly the most significant immigrant city in the United States, and partnerships with organizations like Office of New Americans and Immigrant Powered helped ensure these conversations were multifaceted.

“I was looking at Miami and was really excited to be in a place where it is majority immigrants,” says Daniel. “It didn’t feel like I was foreign here, it just felt like everyone gets how it feels to be different. I felt at home.”

Feeling at home is how we welcome artists into our orbit, and that essential feeling was crucial for this month’s artists who were sharing their deeply personal experiences.

“Just the idea that it was specifically for people who were not U.S. residents was great,” says Marton, who noted that most U.S.-based artist residencies require visas or resident status in order to attend. “It was an open opportunity for people like us, and the programming component was phenomenal because it meant that I could engage with people from the community in a meaningful way.”

“I felt very welcome and safe, which for an immigrant and an artist navigating the art world isn’t always how I feel. The fact that the first thing we do is go to Kathryn’s is very grounding,” says Arleene. “While the residency is certainly part of the art market and industry, it feels wholesome. It’s not having that pressure to be a rock star, we can be ourselves.”

Because the residency was focused on drawing out the particular components that make up the immigrant experience, October’s artists were absorbed into the local community both as artists and as people whose experiences mirrored so many of their own. “I think what was most valuable was how much we were encouraged to talk about our experiences, and I didn’t feel I was singled out or strained for bringing this problem up,” says Daniel. “I felt empowered to talk about my experiences here.”

Dive into their stories and get to know their work.

Arleene’s practice is grounded in profound, unconditional love. With a deep admiration and respect for the sacrifices her parents made for their children, and an overwhelming urge to envelope her family and community in comfort and safety, she creates paintings, mixed media works, and ready-to-wear clothing designed to activate political action. Based on extensive interviews she conducts with the ‘invisible’ communities of migrant farmworkers, Arleene is devoted to ensuring their voices and their stories emerge and are recognized for the contributions they make to American life and society. From her research, Arleene creates heartfelt images that straddle the ideas of visibility and invisibility - often rendering figures whose faces are non-existent or obscured, and clothed or surrounded by the objects that make up their identity to the outside world.

“My work is a documentation of our history and fights against the erasure of our culture and narrative in the United States," she says. Her work is extremely didactic and straightforward, purposely designed to be accessible to the communities she aims to represent. "I want to make something that's legible to my community, not some abstraction that is so far beyond them that they can't understand it and see themselves reflected in it,” she adds.

Using color and material like neon and repurposed clothing, and techniques like painting and embroidery, allows Arleene to reposition ancestral practices within the landscape of contemporary art. The duality of this endeavor mimics that which she experiences as both an undocumented immigrant from Michoacan, Mexico and as a resident of Napa Valley, who has been able to access education and a certain level of privilege thanks to the sacrifice her parents made. “It’s a very unique parallel to be on both sides of that experience, because I act as both observer and participant,” she notes.

With community engagement taking an increasingly active role in her work - projects like SOMOS VISIBLES, commissioned by Art in Action to galvanize participation in the 2020 Census among undocumented workers in California - aim to eliminate a stigma of shame among that community while empowering them to make themselves seen and heard.

In addition to making new work, much of Arleene’s time at Fountainhead was geared toward having the conversations that she believes shed light on what her community experiences on a daily basis. From panel discussions to workshops with partners like the ICA’s Young Artist Initiative, Arleene says the experience created empathy that’s crucial for systemic change. “By sharing really deep parts of my trauma, I was able to allow people to view my community from a different perspective,” she says.

Arleene is focused on creating work that both elevates the experiences of her beloved community while encouraging them to live proudly and openly about the contributions they make. “The work is definitely a door that opens up a larger conversation and empowers people in a different way, giving them the strength to let go of this colonized mentality,” she says.

Victoria is interested in how Western cultures and narratives infiltrate the vernacular of African life, oftentimes displacing local traditions or histories in favor of Westernized trends. With a particular focus on textiles and secondhand clothing that makes its way to Africa - often as ‘waste’ that is then re-sold and worn by local residents - Victoria considers African dependence on Western goods and its impact on cultural identity. The material is also a powerful symbol of the immigrant journey - for Victoria, the clothing retains stories and histories of the people who wore them, and lays the groundwork for an intersectional dialogue about how cultures and peoples travel and shape their identities through the filters of their new worlds.

According to Victoria, much of the work stems from her own experience growing up in Nigeria, traveling frequently as an artist, and later, immigrating to the United States. “I was interested in investigating the perception of the use of local products and an over dependence on Western items,” she says. “At the time I was working more globally and it became about looking at the lopsidedness of the trade system.”

Utilizing secondhand clothing as a primary material (though she does often incorporate other repurposed and sculptural materials) incorporating traditional African methods of textile production like weaving, sewing and dyeing which she learnt naturally while growing up in Nigeria. Combining this with contemporary art-making sensibility, she creates large- scale interdisciplinary projects that question notions of authenticity, cultural identity, and post-colonialism in the context of globalization. Grounded in research, some installations will often be accompanied by a fictional narrative Victoria has created to question how anthropological histories are gathered and reported. In this way, Victoria asks us to reconsider what we know about history and remember that it is often subject to the predispositions and prejudices they might bring to a particular set of people or beliefs.

Victoria’s planned Fountainhead Residency was shifted to a virtual context in light of COVID-19, but she participated in the many virtual discussions held throughout the month. Presenting her work as a lens through which to reconsider migration, Victoria explained how the scale and subject matter of her work is really designed to help viewers pause and consider their privilege.

“I realize that there are people who don’t know anything about the experience of repressed groups in our respective countries and societies,” she says. “Even if just one or two people engage with my work, and they had a moment of rethinking their privilege and the lives they lead, I feel that the work would have served its purpose in that way,” she says.

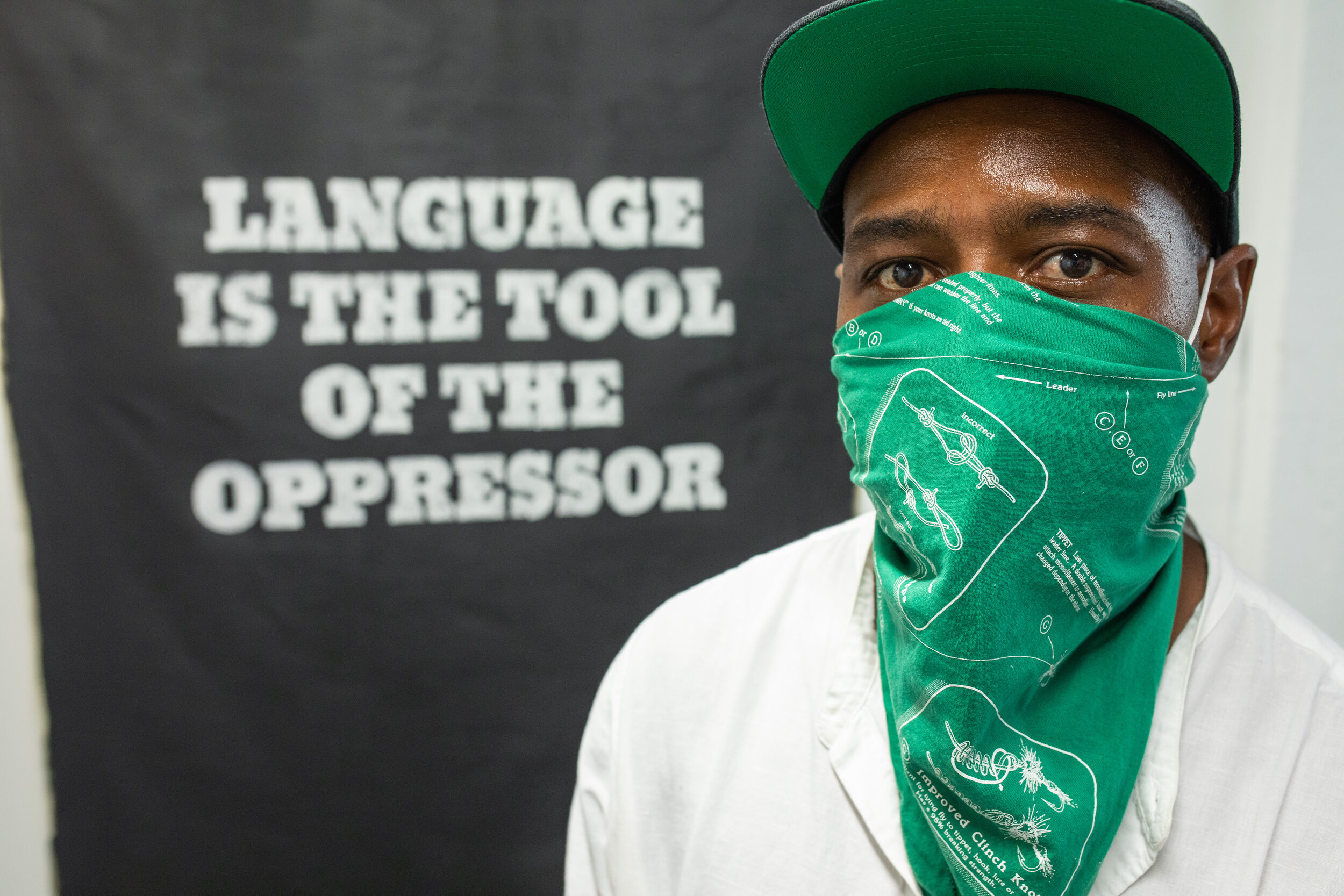

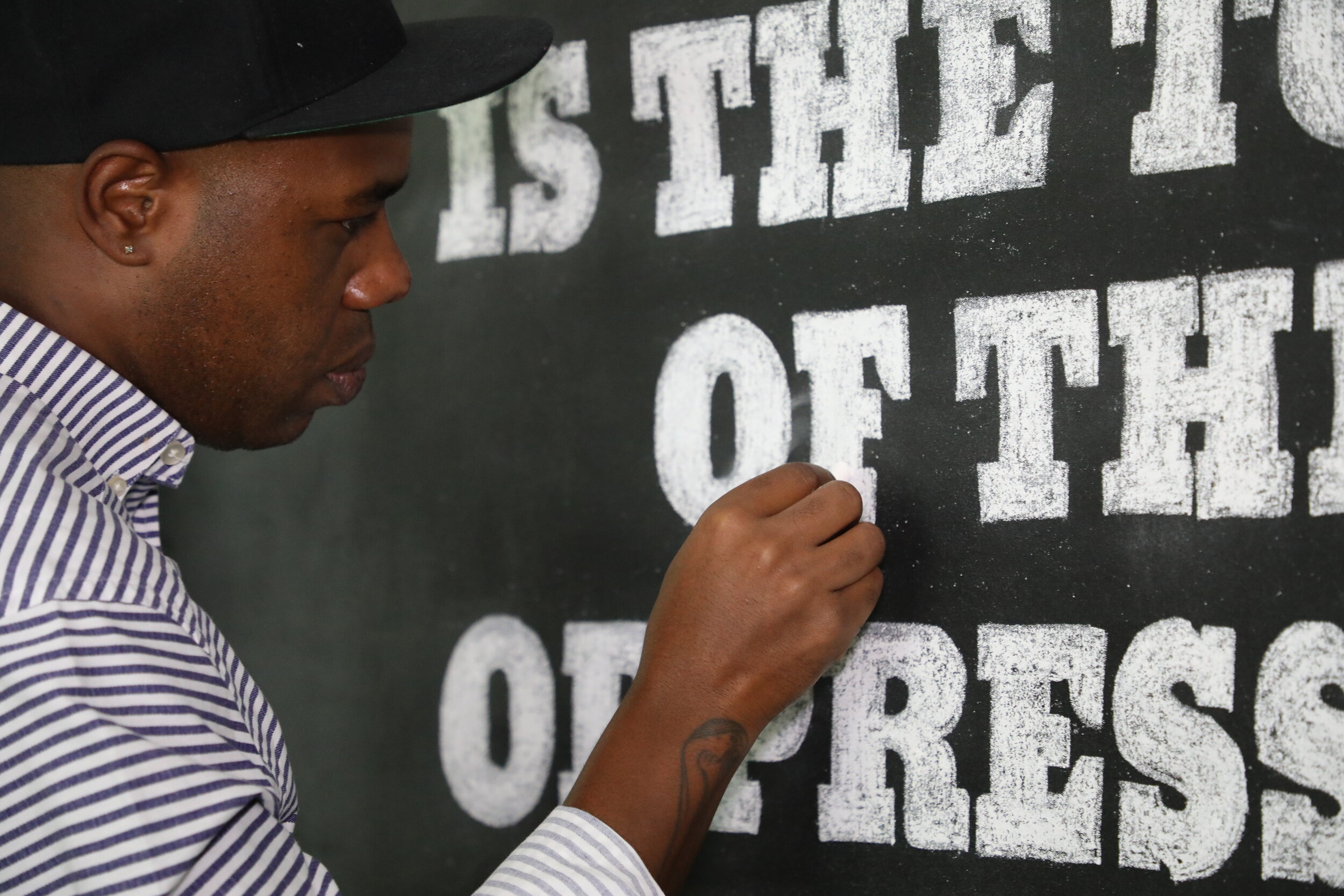

Marton’s work often begins in an archive, and utilizes technology to bring that historical material into the present-day. His work flips the idea of rejection onto people who aren’t used to being denied access to public spaces, ideas, or conversations to create a sense of empathy or at the very least, a balancing of the scale. Traversing North and Central American histories much like Marton himself has intermittently moved throughout his life, Marton traces a lineage of Black liberation in Latin American media and vernacular to how it has influenced Black activism in the United States. Believing that the discourse of Blackness has been dominated by U.S. media and culture, Marton aims to include Latinidad within that dialogue by reminding viewers of Afro-Latin revolutionary contributions throughout time.

“I have this idea that archives are problematic in two senses: one, that they’re read from a nostalgic perspective, and that whoever is the owner of that archive has a specific interest and has made choices about what to leave out,” he says. “There’s a history of Black movements in Latin America that is ingrained and linked to the U.S. movement that it is overlooked. I can create a whole history with an image that traces the movements of Black empowerment in Latin America all the way to Black Lives Matter.”

Born in Costa Rica to a family who migrated there from Jamaica and later, spent some time living in the United States when Marton was growing up, Marton will often excavate familiar pop culture images and showcase how these images can have two different interpretations depending on your vantage point. Centering around representation, Marton is especially interested in exploring how Latin American imagery that sought to empower Blackness was often viewed as offensive by its American counterparts. It creates an interesting frame of thinking that feels both controversial and illuminating.

These images make their way into video and technological works that incorporate sensors to determine what the viewer might be shown. For example, in many works a sensor will be used to detect whether a person is white or black, and then automatically elect what that person is allowed to view. “I really want to encourage certain viewers to think that maybe this is a rigged system,” he says. “That’s where I want to bring them.”

At Fountainhead, Marton created new works that form part of his series Tecnologías Deculoniales, which he says took an interesting new turn thanks to some of the eye-opening conversations he had while in residence. “I had never talked about my work in terms of immigration, and it’s made it more powerful and interesting because it also makes more sense now,” he says. “I think it has more value in this context than how I have been represented in the past.”

Daniel approaches each of his design-based projects as a hypothesis about the human condition. With an interest in relational aesthetics - an artistic theory that emerged in the 1990s to describe art that investigates human relationships and their social context - Daniel creates artworks that bring people together while maintaining a sizable physical distance. His works, often playground-like structures created in joyful primary colors - use optical illusions and lighting effects to bring people to experience intimacy without physically touching, blurring the distances between people.

Almost always exhibited in the public realm, his work reveals the complexity of sharing physical space, encourages understanding despite differences, and contemplates the similarities that invariably connect us all as human beings.

Daniel says his point of departure is his experience as a person of color living in the United States. “I think my interest comes from the fact that some kinds of bodies are able to hold power over other bodies, in terms of being judgmental,” he says. “So my process is basically imagining situations that would bring different bodies closer together and rewiring the hidden dynamics between them. I often do that by altering the perception of distance between yourself and another person, such as something that lets you see someone from a public distance, while also feeling their body intimately in sync with yours.”

Unwittingly, Daniel’s work has become even more poignant and timely considering the present moment. In a world where physical distance has become the norm - and a political climate has created more division than ever experienced in recent memory - encountering one of Daniel’s playful artworks is an opportunity to reflect on how we’re not so different, after all. He purposely makes the work approachable so that viewers don’t feel intimidated by looking someone straight in the eye, hearing their breath, or feeling their body. Tunnels and caves, viewfinders and curtains, and lights and mirrors are frequently employed to provoke a sense of curiosity and discovery that draws viewers in to experience each other in a different way.

Daniel’s time at Fountainhead reminded him that getting closer to his work’s origin story charts a clear path forward for his practice’s trajectory. “Someone mentioned that these structures are a lesson in empathy and that they teach viewers to think about empathy not just in terms of finding similarities between yourself and another person, but rather to see and respect differences,” he says. “So that got me thinking about how to investigate this idea of empathy with my work...since the work really stems from my experience of being an immigrant and a person of color.”